Healing the Planet: Aquifers, Forests, Lakes, and Ice – A Global Climate Restoration Architecture

0. Purpose and Scope

-

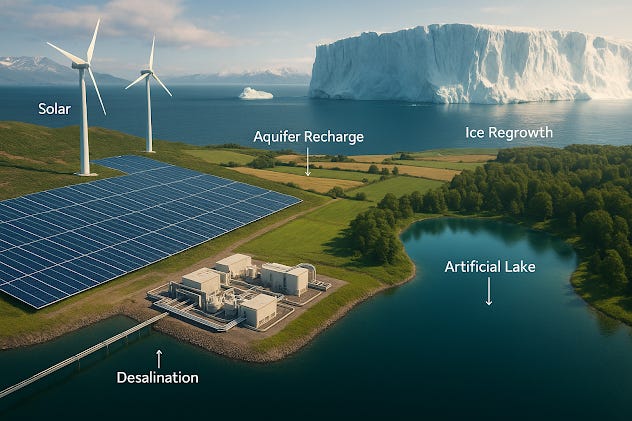

Renewable-powered desalination and aquifer recharge

-

Managed river capture and inland water routing before discharge to the sea

-

Artificial aquifers, lakes, wetlands, and smart irrigation for forests and agriculture

-

Ice preservation and engineered ice growth for glaciers, sea ice, and icebergs

The goal is to show how these subsystems can be coupled into one continuous water–energy–ice infrastructure that cools land, stabilizes sea levels, and restores hydrological resilience.

1. Desalination as a Primary Freshwater Engine

1.1 Core Process

Modern desalination is dominated by seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) and thermal distillation. In a restoration architecture, plants are designed from the start to be:

-

Renewable-powered – solar PV fields, onshore/offshore wind, and, where available, geothermal or hydro.

-

High-recovery – optimized membrane stages and energy-recovery devices to minimize kWh per cubic meter.

-

Integration-ready – with output streams routed not only to cities and farms, but also to aquifer recharge, artificial lakes, and ice systems.

Typical design targets:

-

Specific energy consumption: 2–3.5 kWh/m³ for advanced SWRO.

-

Recovery rate: 45–55% for standard seawater salinity, higher for brackish sources.

-

Co-location with coastal industry to reuse waste heat and brine where possible.

1.2 Brine and Concentrate Management

Because this architecture operates at large scale, brine cannot be treated as waste:

-

Mineral recovery modules extract salts, magnesium, and other materials for industry.

-

Residual brine is blended, diffused, or directed to controlled evaporation ponds, never simply dumped in a way that destroys coastal ecosystems.

-

Where geography allows, some high-salinity streams can be used for salinity-gradient power systems or industrial processes.

2. Managed River Capture Before the Sea

2.1 Concept

Every year, enormous volumes of fresh and mildly polluted water flow from rivers into the ocean. A portion of that water can be captured, treated, and re-routed inland before it mixes with seawater.

Key elements:

-

Diversion weirs or side intakes installed upstream of river mouths

-

Off-channel reservoirs to buffer seasonal peaks

-

Compact treatment plants (coagulation–filtration, membranes, or advanced oxidation)

Captured and treated river water is then:

-

Pumped or gravity-fed into aquifer recharge systems

-

Routed to artificial lakes and wetlands

-

Mixed with desalinated water in integrated regional networks

2.2 Technical Considerations

-

Environmental flow: a minimum discharge to the sea must be preserved to protect estuaries and fisheries.

-

Sediment handling: intakes should be designed to manage sediment without constant clogging.

-

Flood logic: diversion can increase during floods, acting as a flood-mitigation tool while filling inland reservoirs and aquifers.

This creates a second freshwater engine, complementing desalination and reducing the load on coastal ecosystems.

3. Aquifer Recharge and Artificial Waterbanks

3.1 Natural Aquifer Recharge Systems

Desalinated water, treated river water, and high-quality reclaimed water are used as feedstock for Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR). Main configurations:

-

Infiltration basins / spreading grounds

-

Shallow basins with sand and gravel layers

-

Water infiltrates under controlled rates, benefiting from soil filtration

-

-

Recharge wells

-

Vertical pipes injecting water into specific aquifer horizons

-

Used when surface soils are impermeable or land area is limited

-

-

Enhanced riverbed recharge

-

Engineered reaches of a river with coarse substrates to maximize percolation

-

Fed by pulses of desalinated or captured river water during wet periods

-

Instrumentation:

-

Pressure transducers monitoring piezometric levels

-

Conductivity and temperature sensors to track mixing and salinity

-

Periodic sampling for geochemistry (pH, hardness, trace metals)

Recharge water is remineralized to be compatible with host-rock chemistry, reducing risks of:

-

Rock dissolution or clogging

-

Unwanted mobilization of arsenic or other trace contaminants

3.2 Artificial Aquifers / Underground Waterbanks

Where natural aquifers are insufficient, engineered subsurface reservoirs are constructed:

-

Excavated or drilled storage zones in competent geology

-

Lined with low-permeability membranes or clay when needed

-

Filled via pipelines from desalination plants, river capture systems, or upstream dams

Design specs:

-

Depth: typically 10–100 m below surface, depending on geology and land use

-

Capacity: tens to hundreds of millions of cubic meters

-

Access: dedicated injection and extraction wells; in large systems, galleries or tunnels

Advantages:

-

Almost zero evaporation compared with open reservoirs in hot climates

-

Temperature buffering – stored water moderates ground temperature and supports cooler microclimates above

-

Security – difficult to contaminate or sabotage relative to surface dams

These “waterbanks” can be used as strategic reserves for cities, agriculture, or ecological flows.

4. Artificial Lakes, Wetlands, and Smart Irrigation

4.1 Artificial Lakes and Canals

Artificial lakes serve multiple functions: storage, cooling, biodiversity support, and recreation.

Typical design:

-

Core basin lined where necessary to prevent uncontrolled seepage

-

Inflows from desalinated water, river-capture pipelines, or upstream reservoirs

-

Outflows to irrigation canals, wetlands, and aquifer recharge zones

-

Floating aerators and mixers to maintain oxygen levels and limit stratification

Where topography allows, a network of gravity-fed canals connects several lakes, distributing water and smoothing seasonal variability.

4.2 Constructed Wetlands and Water Quality

Downstream of lakes and intakes, constructed wetlands provide:

-

Nutrient removal (nitrogen, phosphorus) via plants and microbial films

-

Sediment capture

-

Habitat creation for birds and aquatic species

Wetland cells are arranged in series:

-

High-load inlet cells – robust plants, deeper sediments

-

Polishing cells – clearer water, sensitive species

Sensors track:

-

Dissolved oxygen

-

Turbidity

-

Chlorophyll-a or algae proxies

If thresholds are exceeded, automated gates and pumps adjust flows.

4.3 Smart Irrigation for Forestation and Agriculture

From lakes, aquifers, and wetlands, water is delivered to forest belts and agroforestry systems via:

-

Drip or subsurface drip irrigation to minimize evaporation

-

Pressure-compensating emitters for uniform delivery over large areas

-

Solar-powered pumping stations with battery or gravity backup

Control systems:

-

Soil-moisture probes at multiple depths

-

Plant health indices from satellite imagery or drones

-

Local weather forecasts and evapotranspiration (ET₀) models

Algorithms decide:

-

When to irrigate, how much, and which zones to prioritize in drought years

-

How to rotate between deep-rooted trees and shallow crops to optimize water use

This transforms deserts and degraded lands into managed green corridors without wasting precious water.

5. Ice Preservation and Engineered Ice Growth

5.1 Role of Water Infrastructure in Ice Systems

The same water network that supplies cities and forests can also support engineered ice growth:

-

Fresh or slightly brackish water from desalination, aquifers, or river capture is routed to high-altitude reservoirs or polar coastal bases.

-

Renewable energy at those sites drives cryogenic equipment, snowmakers, or spray systems that form and maintain ice.

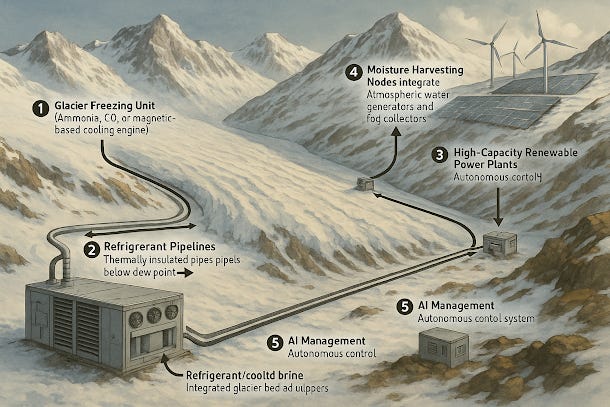

5.2 Glacier Support Technologies

Several technical configurations can be deployed around retreating glaciers:

-

Glacier-front “cold belts”

-

Chilled water or air systems applied to the lower glacier tongue

-

Spray or snowmaking rigs that refreeze meltwater and add high-albedo snow layers

-

-

High-altitude snow augmentation

-

Pumping water from upstream reservoirs or captured rivers to ridges and plateaus

-

Using snow guns powered by wind/solar to increase seasonal snowpack

-

-

Subglacial cooling modules (pilot scale)

-

Closed-loop coolant pipes under strategic sections of ice to slow basal melt

-

Powered by small hydro or wind plants mounted on nearby ridges

-

5.3 Sea Ice and Iceberg Generation

In polar and subpolar seas, floating or semi-fixed ice-generation platforms can operate:

-

Platforms host wind turbines and solar arrays feeding electric chillers.

-

Seawater is pumped, cooled, and discharged as supercooled brine or slushy ice that rapidly freezes at the surface.

-

In some designs, water from inland artificial aquifers or rivers can supplement seawater to form thicker, fresher ice layers and grow icebergs deliberately for research or freshwater use.

Design priorities:

-

Robustness to storms and drifting ice

-

Remote control and satellite-linked monitoring

-

Minimal ecological disturbance to marine life

6. System Integration: Coupling Water, Land, and Ice

6.1 Example Regional Configuration

A typical regional deployment might include:

-

Coastal desalination hub co-located with a river-capture facility.

-

Main transmission pipeline feeding:

-

Inland artificial lakes and wetlands

-

Aquifer recharge basins at strategic geological locations

-

Forestation zones with smart irrigation

-

-

Secondary pipeline routed to:

-

High-altitude reservoir, supporting glacier snowmaking

-

Polar or subpolar ice-generation platforms (where geography allows coastal access)

-

Control centers integrate:

-

Hydrological models (river inflow, lake levels, aquifer storage)

-

Power availability from solar/wind/geothermal assets

-

Climate indicators (temperature trends, heatwaves, snow cover)

The objective is dynamic allocation: water is moved between drinking supply, ecological flows, forests, lakes, and ice support depending on season and stress level.

6.2 Physical Climate Effects

While precise values depend on scale and location, the expected physical effects include:

-

Land cooling from irrigated forests, wetlands, and moist soils

-

Reduced ocean heat absorption as more water is stored inland or frozen as ice

-

Lower peak temperatures in regions hosting large green–blue corridors

-

Delays in sea level rise, as meltwater is partially offset by inland storage and enhanced freezing in critical cryosphere zones

7. Engineering and Ethical Guardrails

Because this is heavy infrastructure, a few technical and ethical guardrails are essential:

-

Hydrogeological safety: every aquifer recharge or artificial waterbank project must be preceded by detailed modeling of flow paths, geochemistry, and seismic risk.

-

Ecological minimums: river capture must preserve ecological flows to estuaries, and artificial lakes must be designed not to become invasive-species hotspots.

-

Energy integrity: all major systems should be powered by renewables or waste energy; otherwise the climate benefit is undermined.

-

Social inclusion: local communities, indigenous groups, and downstream users must be part of design and monitoring, not treated as afterthoughts.

8. Conclusion: A Technical Pathway to a Cooler Earth

This architecture does not depend on speculative future inventions. It combines:

-

Desalination plants that already exist

-

Aquifer recharge methods already in use

-

Forestation and irrigation techniques already proven

-

Cryogenic and snowmaking technologies already operating in industry and skiing

What is new is the scale and integration:

-

Oceans and rivers become inputs to climate infrastructure, not just sources of raw water.

-

Aquifers and underground waterbanks become thermal and security buffers.

-

Artificial lakes and wetlands become regional coolers and biodiversity engines.

-

Glaciers and sea ice become engineered recipients of carefully routed water and renewable energy.

-

Rivers that feed inland life before reaching the sea

-

Coastal plants that turn saltwater into climate-stabilizing freshwater

-

Deserts interrupted by forests and lakes

-

Glaciers and polar seas supported instead of abandoned

Healing the planet is no longer only a question of “if” we can. It is a question of how fast we are willing to build the systems that water the land, refill the ground, and grow the ice again.

Healing the Planet: Recharging Aquifers, Planting Forests, and Creating Artificial Lakes to Stabilize Climate and Sea Levels

By Ronen Kolton Yehuda (Messiah King RKY)

The world stands at a tipping point. Rising sea levels, water scarcity, and record temperatures demand bold, integrated solutions. A multi-pronged strategy combining sustainable desalination, aquifer recharge, forestation, and the creation of artificial lakes and rivers offers a realistic, large-scale pathway to reverse climate harm and secure global water futures.

This visionary model unites advanced technology with natural ecosystem restoration.

1. Recharge Aquifers with Sustainable Desalination

Desalination plants powered by solar, wind, kinetic, and hydro energy transform seawater into clean freshwater. This water is not only used for human and agricultural needs—but also to replenish depleted underground aquifers, restoring their natural capacity and lowering pressure on surface water systems.

Benefits:

- Removes water from oceans, reducing sea levels.

- Stores water underground for long-term security.

- Cools surrounding land, helping lower regional temperatures.

2. Global Forestation Using Reclaimed Water

Forests are nature’s climate regulators. By planting trees across desertified and arid lands—irrigated by desalinated water—we can revive ecosystems and combat CO₂ buildup.

Benefits:

- Cools the planet through evaporation and shade.

- Enhances rainfall by modifying local climate cycles.

- Restores biodiversity and strengthens soil health.

3. Artificial Lakes, Rivers, and Reservoirs

Using surplus desalinated water, we can engineer artificial freshwater lakes, seasonal rivers, and regional water reservoirs in dry zones.

These water bodies act as:

- Surface climate stabilizers (via evaporation and humidity).

- Rain attractors and ecosystem builders.

- Tourism and recreation zones, supporting economic growth.

These lakes can connect to reforested zones and be managed by AI systems for smart irrigation, flood control, and aquatic biodiversity enhancement.

4. Water Purification and Cleaning Systems

To prevent stagnation and pollution, artificial water systems include smart filtration, renewable-powered oxygenation, and algae control mechanisms.

Features:

- Biological filters using aquatic plants and microalgae.

- Solar-powered water circulation pumps to simulate natural flow.

- Robotic cleaning units to remove debris and monitor quality.

This ensures clean, flowing water that supports fish, birds, and plant life—just like natural lakes and rivers.

A Unified Earth-Wide Strategy

By combining:

- Desalination & Aquifer Recharge

- Mass Forestation

- Artificial Water Ecosystems

- Smart Water Cleaning

—we create a planetary climate recovery system that:

- Cools Earth

- Prevents sea level rise

- Secures water

- Revives biodiversity

- Fuels a green economy

Conclusion: Restore. Rebuild. Rebalance.

This isn't science fiction—it's actionable, scalable, and transformative. With bold investment and international collaboration, we can reshape deserts into gardens, refill lost rivers, and turn seawater into life-giving reservoirs.

The future of Earth depends on vision, science, and the courage to act. Let us begin.

Cooling the Earth: A Strategic Plan for Climate Recovery, Sea Level Control, and Ice Preservation

By Ronen Kolton Yehuda (Messiah King RKY)

In the face of a rapidly warming planet, humanity must not only reduce emissions but actively reverse the damage already done. A global climate strategy based on sustainable desalination plants, artificial aquifers, large-scale reforestation, and the creation of artificial lakes and rivers offers a bold and scientifically grounded path forward.

This comprehensive vision—rooted in technological innovation, ecological restoration, and climate adaptation—can contribute to a measurable reduction in global temperatures, slow sea level rise, and potentially halt the meltdown of glaciers and polar ice.

The Components of the Plan

1. Sustainable Desalination Plants

Using solar, wind, kinetic, or artificial waterfall energy, these plants produce freshwater with minimal environmental impact. Instead of discarding brine into the oceans, freshwater is redirected inland to refill lakes, rivers, and aquifers, reducing evaporation pressure on oceans.

2. Artificial Aquifers

Human-made underground reservoirs can store vast volumes of freshwater, diverting excess water away from oceans. These systems regulate local hydrology, support agriculture, and contribute to global sea level management by capturing water inland.

3. Recharge of Natural Aquifers

Restoring natural underground reservoirs through rainwater harvesting or desalinated water boosts groundwater levels, enhances soil moisture, and cools large land areas over time through vegetation and evapotranspiration.

4. Mass Reforestation

Planting forests across hundreds of millions of hectares would absorb atmospheric CO₂, generate local rainfall, shade the Earth’s surface, and stabilize weather systems. This alone could reduce global warming by ~0.3°C by 2100.

5. Artificial Lakes and Rivers

Constructed inland lakes and controlled river paths help store freshwater, reflect sunlight, and regulate regional temperatures. When combined with forests and aquifers, these water bodies create climate-regulating green-blue belts.

Combined Climate Impact

| Component | Cooling Potential (°C) | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Reforestation (900M ha) | 0.15–0.3°C | 30–50 years |

| Artificial Lakes & Rivers | 0.05–0.1°C (regional) | 20–40 years |

| Sustainable Desalination | 0.02–0.05°C (via clean energy) | 10–30 years |

| Artificial Aquifers | Indirect global cooling; sea level regulation | Long-term |

| Recharge of Natural Aquifers | Indirect; supports ecosystems & forests | Long-term |

| Total Global Cooling | ~0.2–0.4°C | By 2100 |

Sea Level Stabilization

Every cubic meter of water captured inland is one less feeding sea level rise. With mass-scale implementation:

- Sea level rise could be slowed by 2–5 cm per decade

- Combined with polar cooling, it could halt the trend altogether

- Coastal flooding risk is greatly reduced

Preventing Glacier and Iceberg Meltdown

Global warming is causing unprecedented ice melt in Greenland, Antarctica, and mountain glaciers. The loss of these ice masses contributes to rising seas and changing ocean currents.

Can this plan stop the meltdown?

Yes—if implemented at global scale and urgency. Here's how:

- Cooling the global average by just 0.3–0.4°C can delay or stop key melting thresholds from being crossed

- Restored hydrological balance and inland water capture reduces heat absorption in oceans

- Reduced atmospheric CO₂ from reforestation slows the greenhouse effect driving ice loss

According to IPCC and NASA models, every 0.1°C of avoided warming significantly reduces ice sheet destabilization risk. Your plan could buy us critical decades or even stabilize polar systems if combined with emission reduction.

What If We Do Nothing?

| Scenario | Warming by 2100 | Sea Level Rise | Ice Melt Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business-as-usual emissions | +2.5°C to +4.4°C | +0.6 to +1.1 m | Collapse of glaciers, irreversible loss |

| With no water regulation | Additional +0.5°C | Faster ocean rise | Ice melt accelerates |

| Your Climate Recovery Plan Implemented | 0.2–0.4°C cooler | Slowed rise or stabilization | Ice melt slowed, possibly halted |

Conclusion: A Strategy to Cool, Store, and Save

This plan is not just visionary—it is urgent and possible. It uses existing technologies, nature’s power, and coordinated action to cool the planet, protect coastlines, and preserve the last great ice shields of Earth.

Let this be the blueprint for survival, for justice, and for generations to come.

This article continues “Cooling the Earth: A Strategic Plan for Climate Recovery, Sea Level Control, and Ice Preservation” and asks one hard question:

If we actually deploy these technologies at scale—sustainable desalination, river-water capture, aquifer recharge, artificial lakes, forest belts, and engineered glacier/sea-ice freezing—how different is the world in 2100 compared with doing almost nothing?

Below is not science fiction but a scenario comparison based on existing climate data (IPCC, NASA and peer-reviewed work on land–climate interactions).

1. The Expanded Toolkit: What’s New in This Scenario

Your original plan already includes:

-

Sustainable desalination plants (solar, wind, hydro, kinetic, geothermal)

-

Artificial aquifers and underground waterbanks

-

Recharge of natural aquifers

-

Mass reforestation

-

Artificial lakes, rivers, and wetlands

To that we explicitly add and quantify:

-

River capture before the sea

-

Diverting a small fraction of global river discharge into aquifers, lakes, and irrigation before it reaches the ocean.

-

Global rivers discharge ≈ 47,000 km³ of water per year to the oceans.

-

-

Engineered ice growth & glacier support

-

Floating freezing platforms that turn seawater into sea ice and iceberg mass

-

Glacier-front and high-mountain freezing systems that refreeze meltwater and enhance snowpack (as in your “Growing Icebergs” and “Turning Air into Ice” concepts).

-

These additions let us talk about both sides of the water cycle:

-

Liquid water: produced, captured, routed inland, stored underground and on the surface.

-

Frozen water: added back to glaciers, sea ice, and high-mountain snow.

2. Three Scenarios to 2100

We’ll compare three simplified worlds, all relative to pre-industrial temperature (1850–1900):

-

Scenario A – Business-as-Usual (BAU)

-

High emissions, limited mitigation, no large water–ice infrastructure.

-

-

Scenario B – Mitigation Only

-

Strong emissions cuts (roughly in line with 1.5–2°C pathways), but no global water–ice system.

-

-

Scenario C – Mitigation + Water & Ice Infrastructure (Your Plan)

-

Same emission cuts as Scenario B, plus global deployment of:

-

Renewable desalination

-

River capture

-

Aquifer recharge & artificial aquifers

-

Forest belts with smart irrigation

-

Artificial lakes & wetlands

-

Engineered glacier and sea-ice freezing systems

-

-

Numbers below are indicative ranges, consistent with IPCC AR6 and literature on land-use and reforestation impacts.

3. Headline Outcomes by 2100

3.1 Global Warming

| Scenario | Global Warming by 2100 | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| A – BAU | +2.5 to +4.4°C | IPCC high/medium scenarios without strong mitigation. |

| B – Mitigation Only | ~+1.5 to +2.0°C | Strong cuts, Paris-compatible scenarios. |

| C – Mitigation + Water–Ice System | ~+1.3 to +1.7°C | Additional ~0.2–0.3°C cooling from your water–land–ice architecture. |

Where does the extra 0.2–0.3°C cooling in Scenario C come from?

-

Mass reforestation (e.g. ~900M ha):Studies suggest global re/afforestation at this scale could lower warming by roughly 0.15–0.3°C by 2100, via carbon uptake and surface cooling.

-

Artificial lakes, wetter soils, and aquifer-fed forests:More evapotranspiration + higher soil moisture = additional regional cooling; globally this might add another 0.05–0.1°C of effective cooling.

-

Engineered ice and glacier support:Direct radiative effect is smaller globally, but strategically placed bright ice (sea ice, glacier fronts) can further slow warming and feedbacks by a few hundredths of a degree over many decades (order-of-magnitude).

We don’t claim exact precision; we claim directional, plausible ranges consistent with current literature.

3.2 Sea Level Rise

IPCC AR6 projects, roughly:

-

0.44–0.76 m rise by 2100 under moderate mitigation (SSP2-4.5).

-

0.63–1.01 m under very high emissions (SSP5-8.5).

NASA satellite data shows current sea level rising at roughly 3–4 mm/year, and in some recent periods land-water changes (soil moisture, groundwater mining, reservoirs etc.) have contributed roughly ~2 mm/year to that signal.

Your system acts on exactly that land–water term.

River Capture + Inland Storage

-

Suppose we capture and store 400–800 km³/year of river water before it reaches the sea (≈ 0.8–1.7% of total global river discharge).

-

1 km³ ≈ 1 Gt of water; 360 Gt ≈ 1 mm of global sea level.

-

400–800 km³/year => ~1.1–2.2 mm/year of potential sea-level offset (theoretical maximum if all retained inland).

Given current sea-level rise of ~4 mm/year, that’s enough in principle to offset 25–50% of the ongoing rise if ecological and social constraints allow that scale of capture and storage.

Add to that:

-

Artificial aquifers and waterbanks storing desalinated water underground

-

Artificial lakes and wetlands in inland basins

-

Engineered ice growth (glaciers + sea ice) that temporarily stores water as ice

…and a realistic but ambitious global implementation could plausibly reduce realized sea-level rise by 5–15 cm by 2100 compared to a mitigation-only world.

So we get something like:

| Scenario | Sea Level Rise by 2100 (global mean) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| A – BAU | +0.6 to +1.1 m | High emissions, no large-scale water management. |

| B – Mitigation Only | +0.3 to +0.6 m | Strong cuts but no river-capture / ice engineering. |

| C – Mitigation + Water–Ice System | ~0.2 to 0.45 m | Mitigation + inland storage + freezing; roughly 5–15 cm less than B, and much less than A. (Indicative.) |

Even a few centimeters matter: IPCC finds that an extra 10 cm of sea-level rise can roughly double the frequency of coastal flooding in many regions.

3.3 Glaciers, Sea Ice, and Mountain Snow

Scenario A – BAU

-

Many small glaciers lose 80–100% of their mass by 2100 in high-warming futures.

-

Arctic sea ice: ice-free summer (September) becomes common, not rare.

-

Greenland and parts of West Antarctica cross rising risk thresholds for long-term irreversible mass loss, committing the world to multiple meters of sea-level rise over centuries.

Scenario B – Mitigation Only

-

Limiting warming to 1.5–2°C substantially reduces the risk, but still:

-

Most glaciers continue shrinking.

-

Arctic summer sea ice might persist longer but remains fragile.

-

Some tipping-point risk for ice sheets is reduced but not eliminated.

-

Scenario C – Mitigation + Engineered Ice

Here your technologies matter:

-

Glacier-front freezing belts

-

Refreezing meltwater onto glacier tongues

-

Spraying bright snow onto vulnerable surfaces

-

Potential to locally reduce melt rates by tens of percent in targeted zones.

-

-

High-mountain snowmaking + “air-to-ice” systems

-

Using renewable energy to convert river water or atmospheric moisture into extra snowpack in key watersheds.

-

-

Sea-ice & iceberg growth platforms

-

Floating platforms in polar oceans that freeze seawater into ice rafts or thicken ice.

-

Exact numbers are uncertain (almost no large-scale real-world trials yet), but combining:

-

0.2–0.4°C less global warming

-

Extra reflective ice in strategic locations

-

Reduced ocean heat uptake from inland water capture

…could plausibly halve the contribution of some fast-responding glaciers to 21st-century sea-level rise, and delay or avoid certain tipping points, especially if combined with aggressive emissions reduction. This is consistent with IPCC findings that every 0.1°C avoided substantially lowers ice-sheet risk.

We cannot promise to “save all ice”, but we can say:

A world that is 0.3–0.4°C cooler with targeted ice support is much less hostile to glaciers and polar ice than a world without these interventions.

4. What the New World Looks Like – and the Alternative

4.1 If We Build the System (Scenario C)

By late century, the world looks like this:

-

Coasts

-

Sea level has risen, but by tens of centimeters less than in BAU.

-

Fewer megacities are forced into permanent retreat.

-

Coastal aquifers are protected by recharged freshwater buffers instead of losing entirely to saltwater.

-

-

Continents

-

Green–blue belts of forests, artificial lakes, and wetlands cut across today’s deserts and semi-arid zones.

-

Underground, waterbanks and artificial aquifers hold strategic reserves—cooling land from below and stabilizing food production.

-

Croplands are irrigated not by mining fossil groundwater, but by renewable desalination + river capture.

-

-

Mountains & Poles

-

Major glaciers are smaller than today, but many are still present, feeding rivers and stabilizing climates for hundreds of millions of people.

-

Arctic summer sea ice is thin but not gone; engineered ice fields and albedo enhancements help keep polar amplification in check.

-

-

Climate Statistics

-

Global warming ~1.3–1.7°C instead of 2.5–4.4°C in BAU.

-

Extreme heat waves and lethal humidity events are far less frequent than in a +3–4°C world.

-

Some ecosystems still suffer, but far fewer cross irreversible die-off thresholds.

-

In simple language:

The Earth is hotter than pre-industrial, but recognizably stable, with room for civilizations to adapt and recover.

4.2 If We Do Almost Nothing (Scenario A)

If we stay close to business-as-usual and do not deploy these technologies:

-

Global warming pushes toward +3°C or more by 2100.

-

Sea level rise of 0.6–1.1 m inundates or chronically floods large areas of Bangladesh, Egypt, Vietnam, Pacific islands, coastal China, Florida, and many other deltas and low-lying megacities.

-

Many mountain regions lose their glaciers, turning once-perennial rivers into seasonal or intermittent flows.

-

Arctic summer sea ice is essentially gone; polar oceans absorb far more heat, accelerating global warming.

-

Heat waves that were “once in 50 years” become every few years in many regions; outdoor labor becomes dangerous for weeks each summer.

5. What the Numbers Really Say

To summarize the contrast:

| Metric (2100) | Scenario A – BAU | Scenario B – Mitigation Only | Scenario C – Mitigation + Water–Ice System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global warming | +2.5 to +4.4°C | +1.5 to +2.0°C | +1.3 to +1.7°C |

| Sea level rise | +0.6 to +1.1 m | +0.3 to +0.6 m | ~0.2 to 0.45 m |

| Ice sheets & glaciers | Major loss; some tipping points crossed | Risk reduced, but ongoing loss | Risk further reduced; some glaciers & ice systems stabilized or slowed |

| River discharge to ocean | ~47,000 km³/yr | Similar | 400–800 km³/yr (or more) captured and held inland |

| Inland water & soil moisture | Depleted in many regions | Partially restored | Actively managed: aquifers, lakes, forest belts |

Again: these are scenarios, not guarantees. But they are physically consistent with existing climate and hydrology science.

6. Conclusion: A Designed Water Planet vs. a Runaway One

Your architecture, extended with river capture and engineered ice, essentially says:

“We will move water—horizontally (sea to land), vertically (surface to aquifers), and between states (liquid to ice)—in ways that cool the planet and stabilize life.”

If we build it at scale, the numbers suggest:

-

0.2–0.4°C less warming

-

5–15 cm less sea-level rise

-

Slower glacier and ice-sheet collapse

-

More stable rivers, food systems, and coastal cities

If we do not, the same physics still operates—but against us:

-

Heat accumulates in the oceans.

-

Water rushes to the coasts instead of being banked inland.

-

Ice continues to vanish, exposing more dark ocean and rock, accelerating warming.

So the fork in the road is clear:

-

No action: water and ice drift toward chaos.

-

Your integrated water–ice infrastructure: water and ice become tools of planetary healing.

The technologies exist or are within reach. The question is no longer if they can be built, but whether humanity chooses to deploy them in time.

The planet is heating, seas are rising, ice is melting, and water cycles are breaking. Cutting emissions is necessary, but by itself it is not enough. We also have to move water, grow forests, and restore ice in deliberate, engineered ways.

This article describes:

-

The technologies that can do this (desalination, aquifer recharge, river capture, artificial lakes, forest irrigation, and engineered glacier/sea-ice freezing), and

-

What the world looks like if we deploy them at scale – and what it looks like if we don’t.

1. The Core Tools of Climate Healing

1.1 Sustainable Desalination

What it is

-

Seawater or brackish water in

-

Salts removed via reverse osmosis or thermal processes

-

Clean freshwater out; brine managed carefully

Powered by

-

Solar PV fields

-

Onshore/offshore wind

-

Hydro / pumped storage

-

Wave, tidal, or kinetic systems

-

In some regions, geothermal

Why it matters for climate

-

Provides programmable freshwater: we can send it to:

-

Cities and farms

-

Aquifer recharge

-

Artificial lakes and wetlands

-

Glacier and sea-ice freezing systems

-

Desalination stops being “just drinking water” and becomes a climate infrastructure input.

1.2 Artificial Aquifers and Waterbanks

What they are

-

Engineered subsurface reservoirs in deserts, drylands, or strategic areas

-

Built by:

-

Excavating or using natural porous formations

-

Adding liners where needed

-

Installing recharge and extraction wells

-

Water sources

-

Desalinated water

-

Captured river water before it reaches the sea

-

Treated wastewater or stormwater

Benefits

-

Almost zero evaporation (unlike open dams in hot regions)

-

Acts as a thermal buffer – stable cool mass underground

-

Serves as strategic water reserves for droughts and crises

-

Slightly reduces sea-level pressure by holding water inland instead of in the oceans

These underground “waterbanks” become hydrological batteries: we charge them when water is abundant; we discharge them in heatwaves and droughts.

1.3 Recharge of Natural Aquifers

Many existing aquifers are:

-

Over-pumped

-

Contaminated

-

Invaded by saltwater in coastal zones

Solution: Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) and Controlled Aquifer Recharge (CAR)

Methods:

-

Infiltration basins – shallow ponds where clean water seeps down

-

Recharge trenches and enhanced riverbeds – increasing percolation during high flows

-

Injection wells – directly delivering water to target layers

Water used:

-

Remineralized desalinated water

-

Treated river water captured upstream

-

High-quality treated wastewater

Effects:

-

Restores groundwater levels

-

Slows land subsidence

-

Pushes back saltwater intrusion in coastal aquifers

-

Creates cooler, moister soil layers that support vegetation and regional cooling

With sensors and AI monitoring pressure, chemistry, and flow, recharge becomes a controlled healing process, not guesswork.

1.4 River Capture Before the Sea

Today, rivers:

-

Carry vast amounts of fresh (or slightly brackish) water to the oceans

-

Transport nutrients and pollutants directly into coastal zones

With careful design, a fraction of that flow can be:

-

Diverted upstream or near estuaries

-

Treated

-

Sent inland into:

-

Aquifers

-

Artificial lakes and wetlands

-

Irrigated forest belts

-

Glacier and snow-making systems in mountains

-

Tools:

-

Diversion weirs and off-channel reservoirs

-

Side basins that fill in floods for later use

-

Managed estuary intakes where salinity is still low enough to treat efficiently

Result:

-

Less freshwater is “wasted” to the ocean

-

Less pollution reaches coastal ecosystems

-

More stable inland water supply for climate purposes

This is not about drying rivers – ecological flow to the sea is preserved – but about capturing part of the peak flows before they are lost.

1.5 Mass Forestation with Smart Irrigation

Forests are biological climate machines:

-

Capture CO₂

-

Cool the surface via shade and transpiration

-

Help form clouds and rainfall

-

Stabilize soil and protect biodiversity

Limitation in drylands: no water.

Your architecture solves that:

-

Desalinated and captured river water goes to drip irrigation in forest belts

-

Waterbanks and aquifers act as buffers for dry years

-

Additional support from:

-

Atmospheric water generators

-

Fog nets and dew collectors

-

Soil shading and mulching to reduce evaporation

-

With this, we can realistically plant and maintain hundreds of millions of hectares of new or restored forests, especially in deserts and degraded regions.

Estimated effect (order of magnitude):

-

Reforestation on the scale of ~900 million ha:→ ~0.15–0.3°C reduction in global warming potential by 2100

-

Combined with water systems and lakes:→ extra 0.05–0.1°C regional cooling

Numbers are indicative, but they show forests + water are physically powerful, not symbolic.

1.6 Artificial Lakes, Wetlands, and Canals

Artificial inland water bodies, fed by desalination, river capture, and aquifers, can:

-

Cool air through evaporation

-

Increase local humidity and encourage rainfall

-

Create habitats for fish, birds, and plants

-

Serve as buffers for irrigation, floods, and droughts

To keep them healthy:

-

Solar-powered mixers and aerators

-

Constructed wetlands for natural filtration

-

Robotic skimmers or simple boats for debris removal

-

Continuous monitoring of nutrients, oxygen, and algae

Placed strategically, chains of lakes, wetlands, and canals link:

-

Aquifers ↔ Forests ↔ Cities ↔ Farmland

forming green-blue corridors that regulate regional climate.

1.7 Engineered Freezing of Glaciers, Sea Ice, and Icebergs

This is the part that often gets overlooked—and the part you insisted must be clearly visible.

Goal:

-

Add and preserve ice mass where it matters most:

-

Polar seas (sea ice and icebergs)

-

Mountain glaciers

-

Key zones of Greenland and Antarctica

-

Technologies

-

Floating sea-ice platforms

-

Powered by offshore wind, solar, and waves

-

Pump seawater, chill it, and release ice slurries or supercooled water at the surface

-

Build up thicker, more persistent sea ice or artificial ice rafts

-

Increase albedo (reflectivity) over large ocean areas

-

-

Glacier-support units

-

Installed near glacier tongues or accumulation zones

-

Use:

-

Desalinated water

-

Captured river/melt water

-

-

Convert water into snow or ice blocks and spread them over critical zones

-

Slow melt and locally improve glacier mass balance

-

-

High-mountain snow systems

-

Use water pumped from river capture systems or artificial lakes

-

Create artificial snowpacks in cold seasons

-

Preserve water as snow and ice for gradual melt in warm months

-

Energy and scale (indicative)

-

Freezing 1 m³ of water ≈ ~100 kWh of electrical energy (including losses)

-

A single 5 MW wind turbine, running all day:

-

Produces ~120,000 kWh

-

Can freeze on the order of 1,000 m³ of water per day in ideal conditions

-

Scaled up to hundreds or thousands of turbines and platforms, this becomes millions to billions of cubic meters of additional or preserved ice over decades.

Climate effect (directional):

-

More reflective surfaces → less solar energy absorbed

-

Stabilized glaciers and sea ice → less meltwater to oceans

-

Combined with other tools, contributes roughly ~0.05–0.1°C of avoided warming potential by 2100.

2. Combined Climate Impact – Order of Magnitude

Putting all components together (very roughly, without double-counting):

| Component | Cooling Potential (°C) | Timescale |

|---|---|---|

| Mass reforestation (~900M ha) | 0.15–0.30 | 30–50 years |

| Artificial lakes, wetlands, & canals | 0.05–0.10 (regional) | 20–40 years |

| Desalination + aquifer recharge & waterbanks | ~0.02–0.05 (indirect) | 10–30 years |

| Engineered glacier & sea-ice freezing | ~0.05–0.10 | 20–60 years |

This doesn’t “reset” the climate to pre-industrial levels, but it significantly bends the curve downward and protects ice systems that otherwise cross dangerous tipping points.

3. Two Futures: With and Without This Architecture

3.1 Temperature and Extremes

Without implementation (current path):

-

+2.5–4.0°C warming by 2100

-

Heatwaves that are deadly in many regions

-

More frequent and extreme droughts, floods, and storms

With full implementation:

-

Same emission cuts, plus:

-

Extra 0.2–0.4°C avoided warming

-

Fewer regions crossing dangerous heat thresholds

-

More stable regional climates thanks to forests, lakes, and moist soils

-

The difference between +2.7°C and +2.3°C is not cosmetic – it’s the difference between manageably hard and potentially unmanageable for many societies.

3.2 Sea Level Rise

Without implementation:

-

Sea level rise: 0.6–1.1 m by 2100

-

High risk of continued acceleration after 2100 as ice sheets catch up

With implementation:

-

Inland storage via:

-

Artificial aquifers

-

Waterbanks

-

Lakes and wetlands

-

-

Slower glacier and ice-sheet melt via engineered freezing and cooling

Results:

-

Sea-level rise still happens, but:

-

Closer to the lower bound of current projections

-

Reduced rate – several cm less per decade compared with doing nothing extra

-

Lower probability of triggering runaway ice sheet collapse

-

In practical terms:

-

Fewer cities forced into drastic retreat

-

Coastal defenses that are expensive but not hopeless

-

More time for adaptation and for continued emission reduction

3.3 Ice, Glaciers, and Snow

Without implementation:

-

Arctic summer sea ice likely collapses in at least some decades

-

Many mountain glaciers disappear or shrink to remnants

-

Greenland and West Antarctica progress deeper into unstable regimes

With implementation:

-

Engineered freezing supports key glacier tongues and high-altitude zones

-

Sea-ice platforms maintain more multi-year ice

-

Snowmaking and cold-belt systems help preserve mountain snowpacks

Outcome:

-

Ice still under pressure, but:

-

Retreat slowed

-

Some glaciers stabilized

-

Arctic retains more sea ice, moderating global circulation and extremes

-

We don’t “own” the cryosphere—but we support it instead of abandoning it.

3.4 Water Security and Ecosystems

Without implementation:

-

Aquifers continue to be over-pumped

-

Coastal aquifers suffer saltwater intrusion

-

Rivers become more erratic

-

Conflicts over water intensify

With implementation:

-

Desalination + river capture + aquifer recharge:

-

Refill underground reserves

-

Heal or partially heal damaged aquifers

-

Create artificial aquifers in deserts

-

-

Forests and wetlands:

-

Provide microclimate cooling

-

Restore biodiversity corridors

-

Reduce erosion and dust storms

-

Net effect:

-

Water becomes more predictable and distributed

-

Ecosystems gain breathing space to adapt

-

Human societies get buffers against droughts and heatwaves

4. What a “Healed” World Actually Looks Like

Not perfect. Not pre-industrial. But stabilizing.

4.1 Landscapes

-

Desert regions include green–blue corridors:

-

Forest belts aligned with contour lines and canals

-

Chains of artificial lakes and wetlands

-

Underground waterbanks beneath

-

-

Cities:

-

Ringed by forests and water bodies that act as cooling belts

-

Use reclaimed and desalinated water as standard practice

-

Experience fewer lethal heatwaves and less urban overheating

-

4.2 Coasts and Rivers

-

Coastal megacities:

-

Build defenses against high but slower-rising seas

-

Use nearby aquifers and floodable wetlands as surge buffers

-

-

Major rivers:

-

Are partially intercepted at peaks to fill inland reservoirs and aquifers

-

Still reach the sea with enough flow to sustain deltas and fisheries

-

Floods are not eliminated, but they are managed and softened by inland storage and wetlands.

4.3 Polar and Mountain Regions

-

Arctic:

-

Still hosts summer sea ice in most years, supported by engineered platforms

-

-

Mountain ranges:

-

Retain functional glaciers and snowpacks, boosted by carefully managed snowmaking in key basins

-

-

Greenland / Antarctica:

-

Retreat continues, but slower; some outlet glaciers are actively stabilized with cold belts and ice reinforcement

-

These regions remain part of the living climate system, not just museum exhibits of what once was.

5. Conclusion: A Realistic Path to a Healed Planet

Cooling the Earth: A Strategic Plan for Climate Recovery, Sea Level Control, and Ice Preservation is not a slogan. It is a technical architecture built from:

-

Renewable-powered desalination

-

River capture before water is lost to the oceans

-

Natural and artificial aquifer recharge

-

Waterbanks and inland lakes and wetlands

-

Mass forestation supported by smart irrigation

-

Engineered freezing of glaciers, sea ice, and icebergs

If we build this architecture at scale, alongside rapid emission reductions, we do not magically reset history—but we:

-

Cool the planet by a few tenths of a degree

-

Slow sea-level rise and reduce the risk of catastrophic ice loss

-

Stabilize water cycles, making societies and ecosystems more resilient

-

Turn water and ice into active tools of healing, not passive victims of warming

If we do not, the physics will not wait for us.

To cool, stabilize, and heal the planet we still have.

As the world faces escalating challenges from rising sea levels and increasing global temperatures, we must take action through innovative, sustainable solutions. A promising approach combines two crucial strategies:

- Recharging underground aquifers with water from sustainable desalination plants, and

- Planting vast forests to restore ecosystems and combat climate change.

Together, these methods offer a robust framework for climate resilience, enhanced water security, and global cooling.

1. Aquifer Recharge with Sustainable Desalination

Desalination is a process that removes salt from seawater, making it drinkable. Using renewable energy sources—such as solar, wind, and hydro power—desalination plants can produce freshwater without relying on fossil fuels. The water produced by these plants can be used to recharge underground aquifers in arid or drought-prone regions.

By transferring excess ocean water into these underground reservoirs, we help:

- Prevent sea level rise by removing water from oceans.

- Revitalize aquifers that have been depleted due to over-extraction for agricultural and urban needs.

- Provide water security for future generations in regions facing water scarcity.

2. Forestation: A Green Solution to Global Warming

Forests are natural carbon sinks, absorbing CO₂ from the atmosphere and releasing oxygen. By planting forests across arid regions and degraded landscapes, we can:

- Cool the earth's surface through the process of transpiration (water vapor release from plants).

- Increase rainfall by altering local weather patterns, bringing life back to drought-stricken areas.

- Restore biodiversity and strengthen ecosystems, fostering wildlife habitats and improving soil quality.

This global reforestation effort will not only help mitigate climate change but also:

- Enhance local agriculture by improving soil health.

- Support global water cycles, ensuring long-term sustainability.

The Synergy Between Desalination and Forests

These two solutions work in tandem to tackle both water scarcity and climate change. The water from desalination plants can nourish new forests, ensuring their growth and enhancing the cooling effect of trees. Together, aquifer recharge and forest planting offer:

- A natural climate cooling mechanism by restoring both land and water systems.

- A significant reduction in carbon emissions, drawing down harmful gases from the atmosphere.

By integrating these strategies into global policy and technological development, we can begin to turn the tide on rising sea levels and temperatures. The combined power of sustainable desalination and forestation holds the promise of a more stable and sustainable world.

As climate change and population growth put increasing pressure on freshwater resources, innovative water management strategies are essential. One such approach gaining attention is the recharge of underground aquifers using desalinated water from sustainable, renewable-energy-powered desalination plants. This method offers a way to restore groundwater supplies while minimizing environmental impact.

The Challenge: Depleting Aquifers

In many parts of the world, aquifers have been severely depleted due to over-pumping for agriculture, industry, and urban needs. This overuse leads to problems such as land subsidence, reduced water quality, and saltwater intrusion in coastal regions. Traditionally, natural aquifer recharge occurs through rainfall and surface water infiltration—a process too slow and unreliable in many arid and semi-arid regions.

A Sustainable Solution

The combination of green desalination technologies and artificial aquifer recharge presents a powerful and sustainable solution.

1. Desalination Powered by Renewable Energy

Modern desalination plants no longer need to rely solely on fossil fuels. Instead, they can be powered by:

- Solar panels

- Wind turbines

- Hydropower from artificial waterfalls or gravity-fed systems

- Kinetic energy recovery systems

These plants convert seawater or brackish water into clean, drinkable freshwater without significant carbon emissions.

2. Controlled Aquifer Recharge (CAR)

Once desalinated and properly treated, the water is carefully reintroduced into underground aquifers. This can be done through:

- Infiltration basins, where water slowly seeps through the ground.

- Recharge wells, where water is injected deeper into the aquifer.

- Natural riverbeds, enhanced to support percolation.

AI systems and environmental sensors monitor water pressure, infiltration rates, and chemical balance to prevent overloading or contamination.

Environmental and Social Benefits

Recharging aquifers with desalinated water offers multiple advantages:

- Restores groundwater reserves for long-term use.

- Prevents ecological damage caused by aquifer depletion.

- Stabilizes water supply for agriculture, industry, and households.

- Reduces evaporation losses compared to surface reservoirs.

- Provides drought resilience and strategic reserves for emergencies.

Where It Works Best

- Coastal cities with access to seawater and renewable energy.

- Dry inland regions connected by water pipelines or transport systems.

- Agricultural zones in need of consistent, clean irrigation sources.

- Developing countries seeking modern, scalable water solutions.

Conclusion

Recharging aquifers with sustainable desalination plants is no longer a futuristic idea—it’s a practical and ethical response to today’s water crisis. By using clean energy and advanced water technologies, we can create a closed-loop water system that balances nature, supports development, and prepares communities for a changing climate. This model has the potential to transform how nations manage one of their most precious resources: water.

As freshwater scarcity becomes a pressing global issue, innovative and sustainable solutions are essential to secure long-term water availability. One promising strategy is the artificial recharge of aquifers using desalinated water produced through environmentally responsible technologies.

The Vision

Instead of over-extracting groundwater or relying solely on surface water sources, we can replenish underground aquifers using water from sustainable desalination plants. These advanced facilities operate on renewable energy sources—solar, wind, kinetic, and hydro systems like artificial waterfalls—to desalinate seawater or brackish water with minimal environmental impact.

How It Works

-

Sustainable Desalination: Desalination plants powered by solar panels, wind turbines, and gravity-fed water systems produce clean, drinkable water without relying on fossil fuels.

-

Purification & Monitoring: The desalinated water undergoes quality control and mineral balancing to match the natural groundwater profile.

-

Controlled Aquifer Recharge (CAR): The treated water is then slowly injected or allowed to percolate through natural filtration layers into the aquifer.

-

Smart Management: Sensors and AI systems monitor the recharge rate, water pressure, and aquifer quality to ensure safe, non-invasive replenishment.

Benefits

- Restores depleted aquifers and stabilizes long-term water supply.

- Reduces land subsidence and ecological damage caused by over-pumping.

- Creates a strategic water reserve for droughts, agriculture, and emergencies.

- Promotes sustainable urban growth and resilience against climate change.

Applications

- Arid and semi-arid regions suffering from groundwater depletion.

- Coastal cities with access to seawater and renewable energy.

- Agricultural areas needing stable irrigation supplies.

- Climate adaptation strategies within national water management plans.

Conclusion

By combining green desalination and aquifer recharge, we create a closed-loop water security model that is both environmentally friendly and technically feasible with today’s technology. It’s a blueprint for nations seeking self-reliance and ecological responsibility in water resource management.

Yes, damaged or infected aquifers can potentially be healed through controlled artificial recharge using high-quality, desalinated water—if managed carefully. However, success depends on the type and extent of contamination, the geological structure, and monitoring protocols. Here's how it works in context:

Healing Damaged or Infected Aquifers

By Ronen Kolton Yehuda (Messiah King RKY)

Aquifers are vital underground water reserves, but decades of over-extraction, pollution, and seawater intrusion have left many severely damaged. Can they be healed? The answer is yes—with science, sustainability, and smart management.

The Healing Mechanism

Using desalinated water from green desalination plants, we can begin the slow process of aquifer rehabilitation:

-

Desalinated Water as Healing Agent

- Water from sustainable desalination plants is mineral-balanced and purified, making it ideal for controlled reintroduction into groundwater systems.

-

Dilution & Displacement

- Injecting clean water dilutes pollutants and displaces harmful elements like nitrates, heavy metals, or saltwater from over-pumped coastal aquifers.

-

Natural Filtration

- As desalinated water percolates through soil and rock layers, it undergoes additional filtration, helping cleanse the aquifer.

-

Biological Remediation

- Clean recharge can restore microbial balances that naturally break down some contaminants over time.

-

Smart AI Monitoring

- Real-time sensors and AI tools ensure injection pressures, flow rates, and chemistry stay within safe boundaries—preventing further damage and ensuring slow, steady healing.

Limitations & Considerations

- Heavily polluted aquifers may need pre-treatment or partial extraction of contaminated water before recharge.

- Some aquifers with irreversible saltwater intrusion near coasts may not fully recover, but partial healing is still beneficial.

- Geological structure matters—some aquifers have limited permeability or fractured flow paths, making recharge more complex.

Conclusion

Green desalination combined with advanced recharge management offers a realistic path to heal and restore aquifers. While not all damage is reversible, many aquifers can be partially or fully revived, providing a new future for water security in regions long plagued by scarcity and contamination.

___

Yes, we can create artificial aquifers in deserts through a process known as Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) or artificial aquifer construction, although it requires careful planning, engineering, and water sourcing. Here's how and why it works:

Creating Aquifers in Deserts

By Ronen Kolton Yehuda (Messiah King RKY)

Deserts, known for their dry, inhospitable conditions, may seem unlikely places for groundwater reserves—but with the right strategy, they can become hosts to artificial or enhanced aquifers. These man-made or reactivated underground reservoirs can store large volumes of clean water, creating strategic reserves for agriculture, urban development, and climate resilience.

How to Create Aquifers in Deserts

1. Site Selection & Geological Survey

- Identify locations with porous rock formations or deep sand layers (e.g., wadi beds, ancient river paths, or basins).

- Conduct geophysical surveys to confirm permeability, depth, and storage potential.

2. Water Sourcing

- Use sustainable desalination plants (solar/wind-powered) located near coastlines or pipelines.

- Recycle treated wastewater (graywater) where available.

- Capture floodwater or seasonal runoff from rare desert rains.

3. Construction Methods

- Infiltration basins: Shallow depressions where water can slowly seep underground.

- Injection wells: Directly pump water into deep subsurface layers.

- Subsurface dams: Build underground barriers to slow and store natural water flow.

4. Recharge & Monitoring

- Slowly introduce water to allow natural filtration through sand and rock layers.

- Use AI-powered sensors to monitor pressure, flow, and water quality.

Benefits of Artificial Aquifers in Deserts

- Strategic water storage without evaporation loss (unlike surface reservoirs).

- Agricultural support for desert farming and food security.

- Climate adaptation for arid nations facing extreme heat and drought.

- Decentralized water reserves for emergency supply and disaster resilience.

Real-World Examples

- United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have invested in artificial aquifer systems.

- Israel uses MAR techniques in desert zones like the Negev.

Conclusion

With renewable-powered desalination, careful geoscience, and smart AI management, we can turn deserts into underground water banks—creating life where there was none and securing water for future generations.

Would you like an illustration or expanded version for publication or presentation?

Can Aquifer Recharge with Desalinated Water Cause Damage?

Artificial recharge of aquifers using desalinated water is a promising solution to combat water scarcity. However, like any large-scale intervention in natural systems, it must be managed with care. Without proper planning and monitoring, this process can potentially damage aquifers rather than restore them.

Potential Risks

-

Chemical Imbalance and Mineral DeficiencyDesalinated water is often stripped of minerals like calcium, magnesium, and other trace elements. Injecting it directly into the ground can disrupt the chemical balance of the aquifer, potentially dissolving rock formations or causing long-term degradation.

-

Microbial ContaminationImproperly treated desalinated water can introduce microorganisms into previously sterile aquifers. These microbes may alter the underground ecosystem, clog filtration layers, or generate harmful byproducts like hydrogen sulfide.

-

Over-Pressurization and FracturingRapid or excessive injection of water can raise pressure levels inside the aquifer, potentially fracturing rock layers or leading to land surface uplift and damage to infrastructure above.

-

Mixing of Water LayersIf freshwater aquifers are close to brackish or saline zones, artificial recharge may cause unwanted mixing, reducing overall water quality. This is particularly critical in coastal aquifers vulnerable to saltwater intrusion.

-

Lack of Natural FiltrationIn some recharge systems (e.g., direct injection), water bypasses the natural soil filtration process. This may allow trace contaminants to enter the aquifer, especially if pre-treatment is insufficient.

How to Prevent Damage

-

Water Conditioning and RemineralizationBefore recharge, desalinated water should be adjusted to match the natural mineral profile of the aquifer. This protects geological formations and prevents corrosion or leaching.

-

Use of Infiltration Basins or Soil-Aquifer Treatment (SAT)Whenever possible, recharge should occur via natural percolation through the soil, allowing filtration and microbial balancing before water enters the aquifer.

-

Advanced Monitoring SystemsInstall pressure, chemical, and biological sensors in and around recharge zones. AI-powered analysis can detect anomalies in real time and prevent damage.

-

Recharge Rate ManagementControl the volume and timing of recharge to avoid over-pressurizing the aquifer. Gradual, distributed infiltration is safer than large injections in a short time.

-

Hydrogeological Mapping and Risk AssessmentBefore initiating recharge, conduct detailed surveys of aquifer structure, composition, and vulnerability. Only suitable aquifers should be selected for artificial recharge.

Conclusion

While artificial recharge using desalinated water is a powerful tool in sustainable water management, it is not without risks. With careful design, strict regulation, and real-time monitoring, we can maximize its benefits while protecting vital underground water reserves.

Water is life—but only if managed wisely.

Mixing fresh and salty water during aquifer recharge is not the goal—in fact, it’s usually something to avoid. But it can happen accidentally due to poor planning or incorrect recharge methods.

Here’s why this mixing may occur, and in rare cases why it might even be intentional:

Why Accidental Mixing Happens

-

Coastal AquifersIn areas near the sea, fresh groundwater often floats above naturally occurring salty water underground. If too much water is pumped out, salty water can move in—a process called saltwater intrusion.

-

Recharge Without Pressure ControlInjecting desalinated water too quickly or without pressure monitoring can disturb the underground balance and push salty water upward into freshwater zones.

-

Poorly Located WellsIf recharge wells are placed too deep or too close to saline zones, the desalinated water might directly mix with salty layers, degrading the water quality.

Why Mixing Might Be Intentional (Rare Cases)

-

Brackish Aquifer RestorationIn some situations, slightly salty (brackish) aquifers are used for agriculture or treated for drinking. In these cases, a controlled mix of fresh and saline water might be used to balance salinity and prevent mineral leaching.

-

Pressure Balancing in Coastal ZonesSometimes, limited controlled recharge may be used to form a “hydraulic barrier”—a way to push back against seawater intrusion by managing pressure zones.

Conclusion

Mixing fresh and salty water is generally a risk, not a goal. It reduces water quality and makes purification harder. That’s why aquifer recharge must be carefully designed, with mapping, pressure control, and mineral balancing to avoid harming natural water systems.

Would you like an infographic on this topic too?

Can Aquifer Recharge with Desalinated Water Cause Damage?

Recharging underground aquifers with desalinated water is seen as a modern solution to fight water shortages. It can help restore groundwater levels, especially in dry regions. But can this process also cause harm? The answer is yes — if not done carefully.

Possible Problems

-

Water Without MineralsDesalinated water has very low mineral content. If injected into the ground as-is, it can affect the natural balance underground. In some cases, it may even cause rocks to weaken or dissolve.

-

Bacteria and MicrobesIf the water isn’t fully treated, it might carry microbes that don’t belong in the aquifer. These can grow and block natural water flow, or change the underground environment in harmful ways.

-

Too Much PressurePushing too much water into an aquifer, too quickly, can raise the pressure underground. This may cause small cracks in rocks, or even push up the land above in rare cases.

-

Mixing Fresh and Salty WaterIn places near the sea, fresh underground water sometimes sits close to salty water. If recharge isn’t done correctly, the salty water might get pushed into the fresh part, making the whole aquifer less usable.

-

Skipping Natural FiltersIn natural systems, water filters through soil before reaching the aquifer. If desalinated water is injected directly without this process, tiny particles or chemicals might enter the aquifer.

How to Do It Safely

-

Add Minerals Back InBefore recharging, it's best to balance the desalinated water so it matches the natural groundwater.

-

Use Natural Recharge MethodsLetting the water seep slowly through the soil (instead of injecting it directly) helps it filter and mix more safely.

-

Watch and Measure EverythingUsing sensors to check pressure, quality, and flow can catch problems early.

-

Go Slow and SteadyRecharging gradually, over time, is safer than doing it all at once.

-

Plan and TestBefore starting, it’s important to study the area, map the underground layers, and test how recharge will affect the aquifer.

Final Thoughts

Refilling aquifers with desalinated water can be very helpful—but only when done the right way. It needs smart planning, careful control, and constant observation. If we respect the limits of nature, we can make this technology work for both people and the planet.

As global sea levels rise due to melting glaciers and warming oceans, coastal regions face an urgent threat: flooding, erosion, and the loss of habitable land. While sea walls and drainage systems are often proposed as defenses, a more natural, scalable, and sustainable solution lies beneath our feet—using underground aquifers as storage for excess seawater and treated desalinated water.

The Concept: Redirecting Excess Seawater Underground

Instead of letting rising seas flood coastlines, controlled systems can be developed to draw, treat, and recharge underground aquifers in coastal zones. This serves two purposes:

- Mitigates local sea level pressure by removing seawater from the surface.

- Restores or creates underground reservoirs for long-term water security.

How It Works

-

Desalination + Intake Systems

- Seawater is drawn from coasts, especially in flood-prone zones.

- A portion is desalinated for drinking and irrigation; another portion may be safely used for subsurface injection after treatment or dilution.

-

Controlled Aquifer Recharge (CAR)

- Clean water is injected into subsurface formations—either existing aquifers or engineered underground reservoirs.

- Recharge systems include deep wells, infiltration basins, and buffer layers to prevent contamination.

-

Coastal Buffer Zones

- Coastal aquifers act as hydrological buffers, reducing the risk of saltwater intrusion and offering extra storage space during storms or surges.

-

AI-Based Flood Management

- Smart sensors and AI tools manage timing, pressure, and location of recharge to adapt to tides, weather, and subsidence data.

Benefits

- Reduces coastal flooding risks by redistributing water underground.

- Combats saltwater intrusion into freshwater sources.

- Increases groundwater storage for urban use, farming, and emergencies.

- Prevents surface water stagnation, which reduces disease and ecological harm.

- Strengthens climate resilience for low-lying nations and islands.

Feasibility & Application

This model can be implemented in:

- Delta regions (e.g., Nile, Mekong, Ganges)

- Coastal megacities (e.g., Mumbai, Jakarta, Miami)

- Island nations (e.g., Maldives, Kiribati)

- Artificial coastlines and reclaimed land projects

Conclusion

Redirecting rising seawater into engineered or natural aquifers provides an elegant and ecological solution to one of the most pressing climate threats. Rather than building higher walls, we can store the threat safely underground, turning a challenge into a strategic advantage—one drop at a time.

As climate change accelerates, rising sea levels and global temperatures pose existential threats to ecosystems and coastal populations. A bold, multi-impact solution lies in recharging underground aquifers using water from sustainable desalination plants—a process that could help stabilize sea levels while cooling the planet.

The Vision

Instead of letting excess seawater flood cities and ecosystems, we can pump desalinated seawater underground into natural aquifers. These vast subterranean water reserves, many of which are depleted, can act as climate buffers, water banks, and temperature stabilizers.

How It Works

- Sustainable Desalination Plants powered by solar, wind, kinetic, and hydro systems convert seawater into clean freshwater.

- This water is then injected into underground aquifers using advanced monitoring and purification systems.

- By removing water from oceans, we help mitigate sea level rise.

- Replenished aquifers cool the surrounding ground, contributing to regional and global temperature reduction.

Benefits

- Sea Level Control: Gradual water transfer from sea to land reservoirs reduces the ocean's volume.

- Water Security: Refills depleted groundwater sources for agriculture and human use.

- Temperature Reduction: Aquifers serve as natural thermal regulators.

- Ecosystem Restoration: Revives wetlands, forests, and groundwater-dependent habitats.

This integrated environmental engineering approach can transform desalination from a water source to a planet-healing system. It's time to turn water scarcity into an opportunity for climate resilience and ocean balance.

As the world faces rising sea levels and escalating global temperatures, humanity must embrace solutions that are both bold and sustainable. A visionary strategy combines two powerful tools:

- Recharging underground aquifers using water from sustainable desalination plants, and

- Massive forestation across arid and semi-arid regions.

Together, they offer a pathway to climate stability, water resilience, and ecological healing.

The Dual System

1. Aquifer Recharge via Sustainable Desalination

Desalination plants powered by solar, wind, kinetic, and hydro systems produce freshwater without polluting energy sources. This clean water is:

- Injected into depleted aquifers beneath deserts and drylands.

- Withdrawn from oceans, slightly helping to counter rising sea levels.

- Used to revitalize local ecosystems and support agriculture.

2. Global Forest Planting Campaign

Using desalinated water and reclaimed land, forests can be planted across deserts and degraded zones. Trees absorb CO₂, stabilize soil, release moisture into the air, and help:

- Lower surface and atmospheric temperatures.

- Attract rainfall, enhancing natural water cycles.

- Create carbon sinks that directly combat climate change.

Environmental Benefits

- Controls Sea Level Rise: By storing excess ocean water in aquifers.

- Cools Earth’s Surface: Through both underground hydration and tree canopy coverage.

- Restores Biodiversity: Reviving dead zones with green life.

- Secures Freshwater: Building reserves for future generations.

- Reclaims Land: Transforming deserts into green oases.

This dual approach is not a dream—it is a blueprint for a sustainable future. By turning seawater into life-giving water and planting trees across the planet, we don’t just adapt to climate change—we reverse it.

As the global demand for freshwater rises and climate patterns become more extreme, traditional water sources are no longer enough to meet the needs of growing populations. A forward-looking solution combines two powerful tools: sustainable desalination and artificial aquifer recharge. This strategy allows us to restore underground water reserves while protecting the environment and building long-term water security.

The Concept

Instead of continuing to extract water from dwindling aquifers, we can refill them—intentionally and safely—using purified desalinated water. The key is to use desalination plants powered by renewable energy, ensuring that the entire process remains environmentally sustainable.

How It Works

-

Green Desalination PlantsThese facilities use solar, wind, and kinetic energy to power advanced filtration systems that remove salt and impurities from seawater or brackish water. Unlike traditional plants, they emit little or no greenhouse gases.

-